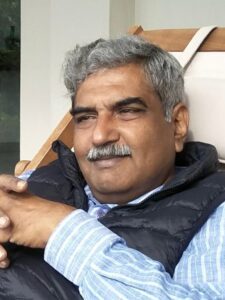

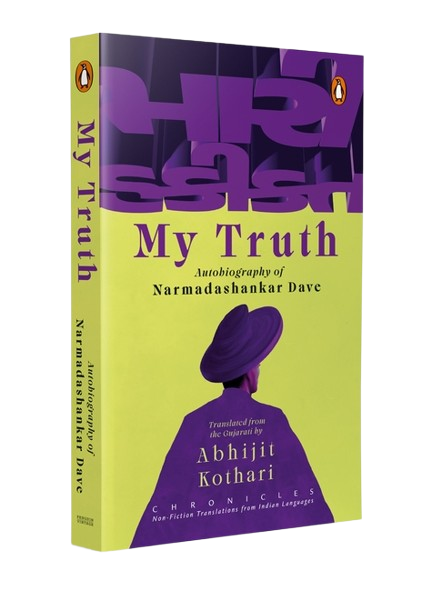

Abhijit Kothari is a literary translator, and combines sociology, business and management in his research and teaching. He lives in Ahmedabad, where he runs his own business. He is also the co-translator of K.M. Munshi’s iconic Patan trilogy with Rita Kothari. Narmadashankar Dave’s “My Truth” is his latest translation. In this interview, he expresses his thoughts on the process of translating “My Truth”, and his reflections on Gujarati language and literature.

Your latest translation, “My Truth”, is Narmad’s autobiography, and is considered to be the first autobiography in the Gujarati language. Translating an autobiography means working with deeply personal stories. What was your initial approach while translating this text?

The important thing was to capture the register of Narmad’s language and style. His Gujarati is in the style of Gujarati spoken in Surat (not something one could capture in the translation). But it was equally important to get Narmad’s motivation and ‘tone’, if you will, in writing an autobiography.

In the original text of “My Truth”, Narmad uses a form which is a mix of an essay and a journal entry, and sometimes a numbering for paragraphs which often does not follow any logic. Is translating an autobiography, which has so many different forms of writing, different from translating a prose piece? How do you think the question of genre and form affects the translation?

The structure of Narmad’s autobiography was unique—perhaps it was the incipient form of the autobiography that determined this structure. I have chosen to retain it to preserve the ‘roughness’, if you will, of the work. In a prose piece – such as a novel – it would be more important to maintain a smooth narrative that would keep the reader absorbed. Translating poetry on the other hand is a far more challenging proposition. In any case, for a translator, the important task is to try to get into the skin of the author (one can only try) and capture the spirit of the work and its language.

What has your relationship with Narmad’s work been like, and how do you place Narmad’s writing in the contemporary context?

Like most Gujaratis, my introduction to Narmad was through his famous poem ‘Jai Jai Garvi Gujarat’ (which offers arguably, the first description of Gujarat in terms of its geographical, religious and cultural boundaries/landmarks). I have not engaged in any detail with Narmad’s literary ouvre – which is vast. My reading about Narmad has been more in the context of the churning of Gujarati society and shaping of thought in 19th century Gujarat. Narmad played a very significant role. He started out as a rebel, someone committed to reform. He took on institutionalised religious and caste-practices. This is the period that the autobiography captures (he was still young when he wrote it). However, he changed his views quite dramatically in the later period of his life becoming what some would call, almost reactionary. He continued writing and it would be worthwhile if these later writings were also to be translated. As for its contemporary context, I would just like to quote Mark Twain “History doesn’t repeat itself, but it often rhymes”.

The 19th century, when Narmad was writing, was a period of great change in Gujarat. The way for this change was opened by important figures, who were, however, mostly upper-caste people. How does your interest in and understanding of sociology inform the act of translating for you? Are there any lesser-known writers in the Gujarati language that you would like to see translated?

This autobiography was to me important in as much as it described several key social movements/episodes in 19th century Mumbai and Narmad’s involvement in them—the role of printing in democratisation of thought, the early colonial vernacular education system, the ‘Maharaj Libel case’, the share mania, reactions to Mahipatram’s travel to England and early attempts at social reform such as widow remarriage.

As someone interested in Business History, the autobiography was also a valuable insight into the role that the merchants of 19th century Mumbai played in terms of the patronage that they provided to writers and poets of the time as well as their role in creating an ecosystem for the production of vernacular literary writing.

There are several works from this period which should be translated – Manilal Nabhubhai’s memoirs for instance, or some travelogues from this period.

You co-translated one of your previous works, the Patan trilogy by K.M. Munshi, with Rita Kothari. How do you collaborate on an exercise in which two people could have different perspectives on what the translation could look like, and what is the process of co-translating like?

This has been an oft asked question and it is rather difficult to describe ethe process—which was a combination of various approaches. There were bits that were entirely translated by one of us and then there were others where we discussed, sometimes argued and then managed to work out the best possible alternative. I think this was possible since both of us agreed on the fundamentals of what translation is and should be.

Among translations that I have enjoyed are Joseph Macwan’s ‘Stepchild’ (Angaliyat) and Ila Arab Mehta’s ‘Fence’(Vaad) translated by Rita Kothari, Kanji Patel’s ‘The Rear Verandah’ translated by Nikhil Khandekar and Nazir Mansuri’s ‘Whale’ (Bokaho) translated by Sachin Ketkar.

What do you hope readers—both Gujarati speakers and those reading in English—take away from this book?

The translation is primarily meant for the non-Gujarati reader and perhaps the Gujarati reader who is not from the area of Gujarati Literature. The autobiography provides a glimpse of Narmad as a sensitive, honest and passionate young man, steeped in his times and yet struggling to break away from what he considers the ‘noose’ of traditions—both social and literary. It also provides information on his relationship with the other towering literary figure of the time—the poet Dalpatram.

Hopefully, the interested reader will come away with some insights into Narmad as a person as well as 19th century Mumbai society, its various significant figures, both literary and non-literary.

What advice would you give to aspiring translators working on autobiographical or deeply personal texts?

I do not consider myself a seasoned translator so as to be able to advise aspiring translators. There are other far more experienced translators who could provide advice. But as stated in my response to Q2, more than just the exact words, it is important to capture the spirit of the work.

Are there any upcoming projects in translation that you are working on that your audience can look forward to?

I have just begun working, with Rita Kothari, on translating works from Gujarati Literature encompassing a fairly wide chronological period (medieval to contemporary) as well as a range of genres –poetry, fiction, travelogues, essays etc. It is early days yet, but it is an exciting project.

About the interviewer

Pakhi Daswani is a student of English Literature at St Stephen’s College, Delhi. Her interests lie in the field of theatre and of writing. She is passionate about literature, language and research. She has worked as an intern at AfterWord, and contributes to the management of their Substack newsletter.